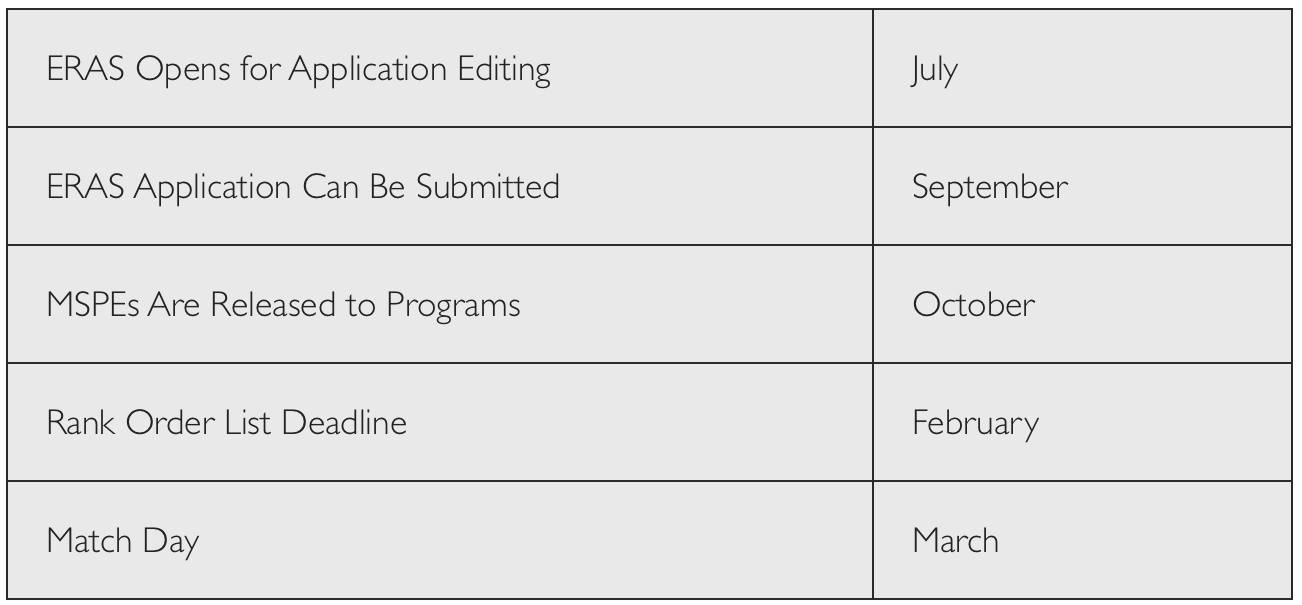

APPLICATION TIMELINE

HOW MANY PROGRAMS TO APPLY TO AND WHICH ONES?

It is best to err on the conservative side -- you can always deny interview invitations, but you will likely not be able to get more interviews if you add applications later in the season. Over the past decade, applicants have been applying to an increasingly higher number of programs. The current average number of applications per applicant is over 65. Recent work has been done by the AAMC to help individuals “Apply Smart”. They recommend that applicants consider the strength of their entire application as well as their personal circumstances. They examined a series of factors, including specialty, Step 1 scores, and applicant type, in order to identify the point at which submitting one more application results in a lower rate of return of entering a residency program. For Otolaryngology, they suggest that applicants with a Step I score >251 should apply to around 33 programs; whereas those with lower scores should consider applying to 40-45 programs. Of course, if there are major deficits in your application, you should probably cast an even wider net. When deciding how many programs to apply to, do not be deterred by application fees. While applying to an extra 10 or so programs can be expensive, this cost is small and necessary in the grand scheme of things.

There are obviously many factors that influence an applicant’s decision on where to apply. Many people have strong preferences for certain geographic areas, city livability, or program reputation for example. In order to hedge bets, applicants are often advised to strategically apply to 1/3 “dream programs”, 1/3 “realistic programs”, and finally 1/3 “backup programs”. It should also be noted that there tends to be geographic discrimination on the part of the residency selection committee when granting interviews. Even if you are a very strong applicant, you will likely find that the majority of the interviews granted tend to be limited to areas to which you have ties, such as your hometown or where you attended undergrad or medical school.

WHAT ARE THE “BEST” PROGRAMS?

Here is the good news; most otolaryngology programs provide excellent training. You can become an outstanding clinician coming from a mediocre program and you can be a horrible otolaryngologist coming from one of the more well-known programs – like with everything, you get out what you put into it. You will see this topic debated on many sites. The reason why no one completely agrees on which programs are the best is because there is no number one! Everything completely depends on what you are looking for. Many people will explore the US News & World Report rankings. While this may place programs in loose tiers, it is important to remember that the rankings are used to rank the department and NOT the residency program -- many of the factors used to determine this ranking seem hardly applicable to the residency experience. Another source of information is the Doximity Residency Navigator.

Since evaluating various residency programs can be a daunting task, we have included a list of “residency selections pearls” to provide applicants with a general point of reference when evaluating programs:

Your goal is to evaluate the residency training program - NOT the department as an academic entity. There are some high-profile departments with mediocre residency training programs. Conversely, there are some low-profile programs with great residency training programs. Beware of programs where most residents seem to have matched there mainly because the program has a big name, but offer little in the way of true insight. Faculty recommendations from staff at your medical school are mostly based on perception of various faculty members at a given institution and less on actual knowledge regarding resident training. Do not assume that well-known faculty are good surgeons/clinicians or dedicated teachers—ask the residents.

Some programs are more demanding than others. In general, the better programs tend to be more demanding. The exception is the very bad program with excessive scut and few residents. There are “high-scut” and “low-scut” institutions. Estimate the amount of scut and divide it by the number of residents in the program. Subtract this value from your educational experience.

Experience from program-to-program is most variable in the following areas: facial plastic surgery, otology, advanced pediatric otolaryngology, and laryngology. Favor programs that let you do MORE THAN tubes/tonsils and other basic procedures as early as possible.

If you plan on an academic career, it truly is helpful to train at a program with many faculty (more connections), a strong research base (more opportunities to write papers), and a high-profile reputation. If you intend to pursue fellowship training, these factors will also increase the chance of landing your first choice. If you can find a good residency training program that is at a solid institution, this is the best scenario no matter what your career plans might be.

If you intend to pursue a career in private practice, you will be well served if you train at a program with at least 1 dedicated rhinologist, facial plastic surgeon, and laryngologist. Particularly strong training in these areas will serve you well in private practice. It is generally better to learn these particular skills from a specialist than otherwise. For example, you probably do not want to learn sinus surgery from surgeons who do it “on the side”.

When a program claims to have an extensive pediatric experience, investigate whether or not that means lots of tubes and tonsils or other more advanced procedures such as airway reconstruction, craniofacial surgery, or neck mass excision. Is there a children’s hospital? The most important pediatric otolaryngology skill to acquire is evaluation and management of the pediatric airway - especially airway endoscopy, tracheotomy, and management of the pediatric patient with a tracheostomy.

Although most programs have at least one otologist, the resident experience is widely variable from program to program. Many programs afford very poor otologic surgical training, even at good institutions. A very good program will prepare you to confidently perform the following procedures: tympanoplasty, canal-wall-up and canal-wall-down mastoidectomy, ossiculoplasty, and middle ear exploration. A great program will also prepare you to perform stapedectomy/stapedotomy, cochlear implantation, labyrinthectomy, and/or endolymphatic sac procedures. It is very rare that a resident would learn to perform advanced neurotology/skull base procedures in residency such as the middle fossa approach, vestibular nerve section, or skull base tumor removal.

A good experience in head & neck oncologic surgery affords the trainee absolute comfort with the clinical evaluation and decision making regarding all head and neck cancer subsites. A very good surgical experience will include broad exposure to the following procedures: neck dissection, parotidectomy, thyroidectomy, parathyroidectomy, total laryngectomy, resection of oral tongue and floor of mouth tumors, and approaches to all deep neck spaces. A great program will teach you endoscopic laser resection of laryngeal and oropharyngeal tumors, transoral robotic surgery, open partial laryngectomy techniques, open approaches to remove tongue base tumors (mandibular swing, transhyoid), mandibulectomy techniques, partial tracheal resection, open surgical approaches to nasal/sinus tumors (lateral rhinotomy, maxillectomy), and/or basic reconstructive techniques (pectoralis flap). Finally, a smaller number of programs will provide extensive experience in removal of advanced skull base tumors or microvascular reconstructive techniques.

A good experience in laryngology includes basic thyroplasty techniques, injection laryngoplasty, and transoral resection of benign and malignant laryngeal lesions using both microsurgical and laser techniques. A great experience in laryngology includes the use of Botox, care of the professional voice, and/or adult airway reconstruction.

A good experience in facial plastics includes various rhinoplasty techniques, familiarity with most local reconstruction flaps in the head and neck, all open approaches for craniofacial trauma, and blepharoplasty. A great experience in facial plastics includes competence with brow lift (open and endoscopic), mid-face lift, face-lift, facial reanimation techniques, facial peel/resurfacing techniques, and cleft lip/palate repair.

A good eperience in rhinology includes basic functional endoscopic sinus surgery (middle meatal antrostomy, ethmoidectomy, sphenoidotomy, and frontal sinusotomy), and septoplasty. A great rhinology experience encompasses frontal sinus drillout, osteoplastic flap, endoscopic orbital decompression, and transnasal endoscopic approaches to the pituitary gland and skull base.

A great experience in general otolaryngology and sleep surgery includes advanced techniques for sleep apnea (tongue base reduction, genioglossal advancement, hyoid sling, LAUP), multiple techniques for sinus surgery (usually requires learning from multiple faculty members), cricopharyngeal myotomy, Zenker’s repair, and/or various in-office endoscopic procedures.

No program graduates residents that cannot perform a myringotomy with tube insertion, tonsillectomy & adenoidectomy, or septoplasty. Subtract these procedures, as well as endoscopy from the surgical experience if you want a true impression of the surgical volume. Be suspicious of programs with a “huge peds experience” if that means 300+ tubes and 200+ adenotonsillectomies as this is overkill.

Almost every resident thinks that their own program provides great training—even if it is not the case. When you interview, seek out residents that seem similar to you (e.g., married vs single, same hometown, common career plans, similar personality)—put more stock in the opinions of these individuals. Seek out programs where the residents are clearly enthusiastic about and happy with the faculty and their training.

Lastly, you will hear a lot of rumors on the interview trail—many of these are incorrect. Put little stock in the impressions of persons who do not have first-hand knowledge (in order of reliability: 1) student at a given institution, 2) student who visited a given institution, 3) student who interviewed at a given institution). Again, secondhand info is often incomplete or frankly incorrect.

WHAT ABOUT THE 7-YEAR RESEARCH TRACKS?

There are several programs that offer additional funded research years for those applicants that are especially interested in incorporating significant research into their future careers. The structure and enrollment of these tracks vary from program to program. The most common way programs integrate research time is by offering a separate, distinct residency research track that must be applied for separately from their traditional 5-year track in the ERAS system. Usually these programs involve two extra years of dedicated research time placed in between the PGY-2 and PGY-3 years. A second, less common way that programs may integrate extended research time into the curriculum is through having “optional” research years available for already enrolled residents. Finally, some programs have decided to integrate a full additional year of research into their curriculum for all residents at the program.

The common advice given to applicants regarding the 7-year research track is to only apply if you are sincerely interested in research. While this seems like common sense, the competition for these spots is usually less fierce, and applicants commonly view these positions as a “plan-B” in case a spot at the 5-year residency program does not pan out. These positions can provide outstanding research opportunities to the interested candidate but an extra two years can be painful if you are not completely sold on research. During your interviews, applicants are sometimes asked, “are you applying to the research track as a backup or are you sincerely interested?” If you apply for these positions, be prepared to explain your motivation for the position.

HOW TO GET INFORMATION ABOUT SPECIFIC PROGRAMS?

There are many resources available to get information regarding specific programs. Our website has a page dedicated to each program containing links for the department in hopes of centralizing much of this data for you.

The first place to look is the department website. Some programs have elaborate sites that spell out everything, while others have no more than a couple generic pages. The AMA Residency and Fellowship Database provides another resource with information about every accredited otolaryngology program. Do not be afraid to ask residents, faculty, and your advisor about various programs - the field is surprisingly small and you might be amazed at the wealth of information you can obtain in this way. Finally, website chat forums can be extremely helpful to get the inside scoop on programs. Just be skeptical about the many unsubstantiated rumors that often find their way into most chat forums.

PERSONAL STATEMENT

A well-done personal statement will never by itself get you into a program, but a poorly written one can definitely keep you out. As with authoring any document, you must know your audience. You are not writing to an eagerly awaiting group of people, who will cherish and ponder every last word written. You are writing to a group of busy faculty members who have already skimmed hundreds of essays before they got to yours! Make it easy on them and give them what they want – nothing more, nothing less. There are many great online resources dedicated to writing the personal statement (e.g., Medfools, UNC). Here are some general points to keep in mind:

DO NOT BE WORDY! Say what you mean with the least words possible - no rambling. There are varying opinions on the ideal length but probably around one full page is perfect. For better readability, avoid using long convoluted sentences.

Start with an attention grabbing introduction, and focus the meat of the essay at the beginning and the end. You will be hard pressed to find a program director that has the time to spend more than 45 seconds to read each essay on the first go around. It is a well known fact that when reviewers skim essays, they will often read the opening couple sentences to determine if it is worth reading. If it is, they will go to the summary or closing paragraph.

There are many correct ways to write an essay, but generally you must include the following key elements: why you are interested in the field; what you have to offer over the other applicants; and vaguely, what your career goals are (e.g., where do you see yourself 10 years down the road). Make sure that you back up any claims of personal traits with specific examples (e.g., I possess outstanding leadership skills. When I was in the Gulf War I successfully led a group of 4 navy seals on 5 recon missions).

Focus on your strengths! This is a time to sell yourself. Do not use this space to make excuses for holes in your application; however if there is a serious challenge that you learned from and overcame, this could serve as relevant material.

Use spell check, correct all grammar mistakes and then, when you think you are nearly finished, ask for a critique from your advisor and possibly other residents.

LETTERS OF RECOMMENDATION

Having outstanding letters of recommendation is crucial to a solid, well-rounded application. The following question then remains: what constitutes an exceptional letter? A good recommendation letter goes far beyond the obvious “this medical student walks on water” type letter. First, since the field of academic otolaryngology is relatively tight-knit, letters of recommendation from within the specialty are preferred over letters from other fields such as general surgery or internal medicine. Second, it is usually blaringly obvious to the reader whether or not the author of the letter really knows the student. Letters from faculty that can speak convincingly about your character, hand-eye coordination, or work ethic are given much more weight than those that merely include a list of your personal accomplishments read off from a furnished CV. Third, if at all possible, recommendations from prominent people in the field can be very helpful.

You will need a minimum of 3 letters of recommendation with one from the chairperson and/or program director of your home program. Not having a letter from your chairperson is often considered a red-flag in an application, so make it a priority to at least meet with them once to express your interest in the field and ideally scrub-in on a couple cases with them on your sub-internship so that they get to know you. The other 2 to 3 letters can come from your specialty advisor, research advisor, or other clinicians you spent significant time with during your sub-internship. If you feel that you performed exceptionally well on an away rotation, obtaining a letter from the chairperson of another institution can be a strong addition. It is best to ask for letters during or immediately after you have completed your rotations so that those writing the letters will have you fresh in their mind.

Some may disagree, but it is generally best to check the “I forego my right to view this letter” box when asking for the letter. If you really are afraid of what they will write about you, you may be asking the wrong person. It is always okay to ask for the letter in such a way as to allow the person a graceful “out” if they will not be able to write a less than great letter (e.g., “Do you feel you know me well enough to write a strong letter of recommendation on my behalf?”)

Finally, when you do ask for the letter, make sure to provide the person with all the things they need to make the process easy and fast. Give them an updated CV, a personal statement if you have it, and the accompanying ERAS LOR form. One of the most common causes for incomplete applications is an unsubmitted letter of recommendation. This is yet another reason to ask for your letters immediately following rotations to allow the authors adequate time to finish them.

The Otolaryngology Program Directors’ Organization currently recommends a Standardized Letter of Recommendation (SLOR). The content of this letter is available for viewing at the following link and will give you an indication of what your letter writers will be looking for from your CV and performance in order to complete a letter on your behalf.

CONSTRUCTING THE CURRICULUM VITAE (CV)

It is a good idea to put together your CV before application time arrives. Even though the ERAS application automatically constructs your CV (they refer to it as the Common Application Form (CAF)) with the data you have entered; putting together a CV early allows more time for fine-tuning. Additionally, you will likely need to give a copy to the programs you are applying to for away rotations and you should also be giving a copy to every person you ask for a letter of recommendation.

Because the recipe for constructing a CV is rather formulaic and there are already many good websites that describe this (e.g., Dartmouth, UNC), we have decided to forgo the fine details and to provide you with the most important things to remember:

DO NOT LIE OR OVER EXAGGERATE! YOU WILL GET BURNED! There are countless stories of how applicants fabricated certain details of the application only to get burned later. Unless you are an awesome liar it is fairly easy during an interview, when you are already nervous, for an interviewer to smell out a fib. You would be surprised about how many applicants will lie even about the most mundane things. One story comes to mind regarding an applicant who fibbed on his CV about being able to play the guitar. Sure enough, at the second program the applicant interviewed at, an interviewer had a guitar in his office and asked him to play. Talk about watching a train wreck happen! This also goes for publications and research. Provide the correct author sequence and do not indicate something was accepted or published if it was not.

Limit the amount of information you include to only the most important details and do not enter redundant facts. Unless you were a PhD in a previous life with tons of publications, try not to exceed 2 pages max. By including little things like volunteering a day with the Red Cross, not only will you bore the reader, you will detract from the more important things and in general this will decrease the quality of your CV.

Proofread it, then proofread it again, then have someone else proofread it, and then proofread it again! When you are staring at a paper for 8 hours straight it is extremely easy to make small errors. After you are done, let it sit for a week and look it over again. You should maintain a consistent format throughout the document, there should be no misspelling or punctuation errors, and your words should be strategic and concise! Anything less will hurt you.

WHEN TO SUBMIT THE APPLICATION?

Ideally, you should aim to submit your application within a week of the scheduled application period. Applicants commonly ask whether it is advantageous to delay the application if they are expecting a publication to be accepted or some other noteworthy CV addition. The general rule is, unless it is the Nobel Prize, do not wait. By getting in your application early, you will maximize your chances of getting the most number of interview offers and the best interview date options for each offering program. If you do have a significant addition such as AOA, or accepted publications, you can always send updates to programs at a later time.